Welcome to Maid Spin, the personal website of iklone. I write about about otaku culture as well as history, philosophy and mythology.

My interests range from anime & programming to mediaevalism & navigation. Hopefully something on this site will interest you.

I'm a devotee of the late '90s / early '00s era of anime, as well as a steadfast lover of maids. My favourite anime is Mahoromatic. I also love the works of Tomino and old Gainax.

To contact me see my contact page.

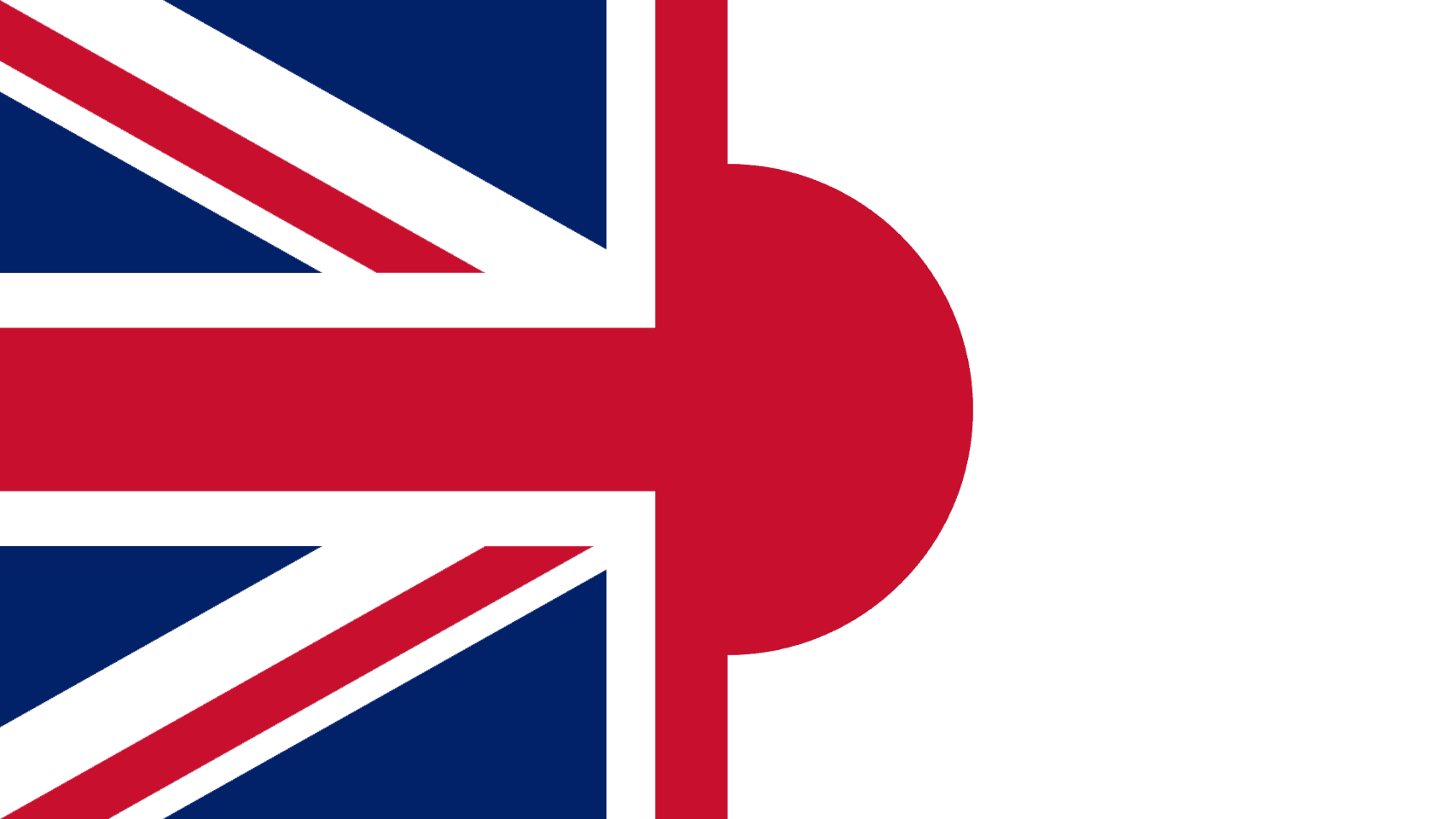

To preface this post with a little sobriety, it is clearly ridiculous to liken the Christianity of our Church with the paganism of Japanese religion, particularly on any theological level. I will not be attempting to do so. Their mutual incompatibility is evident through each's respective history within the other's archipelago, be that the Martyrdom of the Twenty-Six in Japan, or the utter lack of Shinto influence within Britain (Numbering 1,344 in the 2021 census, considerably fewer than "Scientology" or "Witchcraft"). I am instead pulling together threads of similarity in their respective roles and positions within the cultural, societal and historiographical tapestries of "England" and "Japan".

The principle point around which this comparison pivots is that of the Monarch. Both the King and the Emperor are centres for public and private life, with their roles massively important for the justification of each state's existence. Both the Crown and the Chrysanthemum Throne are real manifestations of the nation, despite both being separated from the actual machinations of politics. And although both are positioned at the head of state, the domains over which they exercise their divine rights and responsibilities most dramatically are as the heads of their respective churches. In effect they both hold the position of "Pontifex Maximus", supreme priest and absolute necessities for the functioning of the state. King Charles is of course head of the Church of England and acts as the most important officiary for religious ritual, appointing the Archbishop of Canterbury as chief spiritual advisor. This system is rare within Christendom, scant few Western countries still retain a "state religion" at all, and only England (not the rest of the UK) along with Denmark & the Vatican have state churches who's supreme authority sits with the office of head of state. This places the King, and to a lesser extent the Royal Family, in the position of a conduit between the English and God, the closest point of contact to the world of the divine.

Meanwhile in Japan the disestablishment of Shinto as the official "state religion" was part of the instrument of surrender enforced by Gen. MacArthur in 1945, but as with many of the capitulations, the Japanese civil service wormed its way around such regulations with the political tact of Humphrey Appleby. The Emperor remains the de facto head of Shintoism, as its chief priest responsible for the patter of regular holy days and rituals, both public and private. Another postwar capitulation was that Emperor Showa was made to renounce his status as a kami through the highly controversial "Ningen-Sengen" (Humanity Declaration); however after the American occupation ended wily Shinto priests developed the "Akitsumikami-Arahitogami Solution". This reasons that the Emperor declared himself not a "akimitsumikami" (incarnation of a kami), but never renounced his claim to be an "arahitogami" (a living kami). Broadly speaking this means that it is ritually inadmissible to deny the Emperor's continuing divinity, effectively neutralising that aspect of the constitution in the eyes of the state, and even moreso in the eyes of the Japanese people.

As alluded to, this monarchic keystone to religion has cascading consequences to the broader nation, both to the state and the culture. Apart from those countries populated principally by Englishmen, nowhere has the Westminster System so seamlessly been implemented than Japan. Adopted as part of the Meiji Restoration in 1890, the modern Japanese state was constructed in close alignment with British advisors. The bicameral chambers allows the highly structured feudal system to retain its importance within a democracy; the constitutional position of the monarch allows the Emperor to retain (or in this case regain) a central position without dirtying his hands with politics; the stringent system of legal ascent allows the complex system of civil servants to have total control of any area the government's eyes are not focused. An altogether similar structure of government for an altogether similar structure of society. Furthermore the nations' respective churches became integral to their states. Both act as a "religio publica": frameworks around which official ceremony is conducted. The rituals of the British state are couched in rich Christian tradition, with the religious rituals of the political, the judicial and the military all being absolutely required to continue for self-perpetuation. This is true also for much of the medical world and within the school system, however in recent years these have been somewhat secularly diluted (if only nominally). Similar statements can be said about Japan, although restricted moreso to acts of offering and shrine visits than the oathtaking, hymns and prayer of England.

Religion in England and Japan have both been influenced by the underlying insecurities of each nation, namely spurred by the influence of more powerful continental entities next door. England resisted the Frenchification of Catholicism for the first half of the second millennia, and separated itself entirely from the continent theologically for the second. Minor differences in how religion was performed were exaggerated as a means of self-preservation against a more potent neighbour, until Henry VIII's reformation and the establishment of the first major independent church in Western Europe. Anglicanism is peculiar within the resultant churches of the Protestant Reformation, as it claims to be everything the Roman Church is and more. Anglicanism is catholic, orthodox and protestant simultaneously. It claims a universality on par with anything found on continental Eurasia, maintaining the mandate of apostolic succession (that being a continuous line of bishops consecrated by one of the twelve apostles). In Japan we see this play out through the incorporation of Chinese "religions" into the mass of Shintoism. Buddhism was introduced into Japan around the same time Christianity was to England, which maintained power through isolated monastic institutions akin to those found here at that time. During the 13th century Japan underwent its own "protestant reformation", spurred on by encroaching pressure from China to conform more closely with traditional Buddhist doctrine. The native Japanese sect of "Zen" was embraced by the nobility in rejection of continental influence, and melded with Shinto ways of life to create a form of Buddho-Shintoism that could be accepted by the general Japanese populace for the first time. Just as Anglicanism is a peculiarly English interpretation of the divine, so is the Shinto-Zen-Buddhism amalgamation of Japanese. This influence of realpolitik on culture bled into the perennial English Euroscepticism which resulted in Waterloo, World War II and Brexit alike, but also into a strong antidisestablishmentarianism that is accepted by every major political force today. "We are England because we are not France", "We are Anglican because we are not Catholic". Japan alike has less than warm ties with her neighbours, the influence of China being so strong that it must be staved off with a degree of national contrarianism, "Sinicism with Japanese characteristics" as it were.

So far I have discussed the verifiable structures of each country, but next I want to stray into the murky waters of anthropological observation. We are all eager to see ourselves reflected in every surface, and when discussing cultural or religious practices not necessarily laid out in canon it is hard to draw the line between what is actual and what is a fantasy. In part two of this post I want to show how the English and Japanese have both constructed a spiritual framework around themselves like a beaver does a den, rather than accepting spiritual axioms wholesale like a fox's den. In a manner the Church of England is, through the words of historian Prof. David Starkey:

"A form of English Shintoism. The English worshipping themselves."