Welcome to Maid Spin, the personal website of iklone. I write about about otaku culture as well as history, philosophy and mythology.

My interests range from anime & programming to mediaevalism & navigation. Hopefully something on this site will interest you.

I'm a devotee of the late '90s / early '00s era of anime, as well as a steadfast lover of maids. My favourite anime is Mahoromatic. I also love the works of Tomino and old Gainax.

To contact me see my contact page.

There is a deep chasm between the "experiences" of a Christian Church and Muslim Mosque. It can be quantified in many ways such as architectural form, materials used, natural illumination, or the ambience of sound & smell; but the thing which struck me most pressingly was rather the embellishing decorations. When you enter a great cathedral, or a tiny rustic church for that matter, yes you will be struck initially with the basic structure of the building, but the vast majority of your visit will be focused on the ornamentation. Stained glass windows of saints, illustrations of the Stations of the Cross, supine statues memorialising local lords & bishops. These things make up the bulk what a church has to tell you: while its overall form may be its personality, these extras are the stories which make it personable. So as with the traditional crucifix: the cross-shape is immediate and symbolic, but the narrative and emotion of it is held in the stricken figure pinned to it. If I visit a church empty of such human ornamentation (as I understand is more common in Scotland and other Reformed elsewheres), I struggle to understand it as a "house of God", rather a "monument to God". Maybe its because I am not as in communion with pure form than others may be, but I can't relate to a church which has no human element, and I mean that literally. The figure of man is vital for us, as men, to build relationships. Hence why we personify the world.

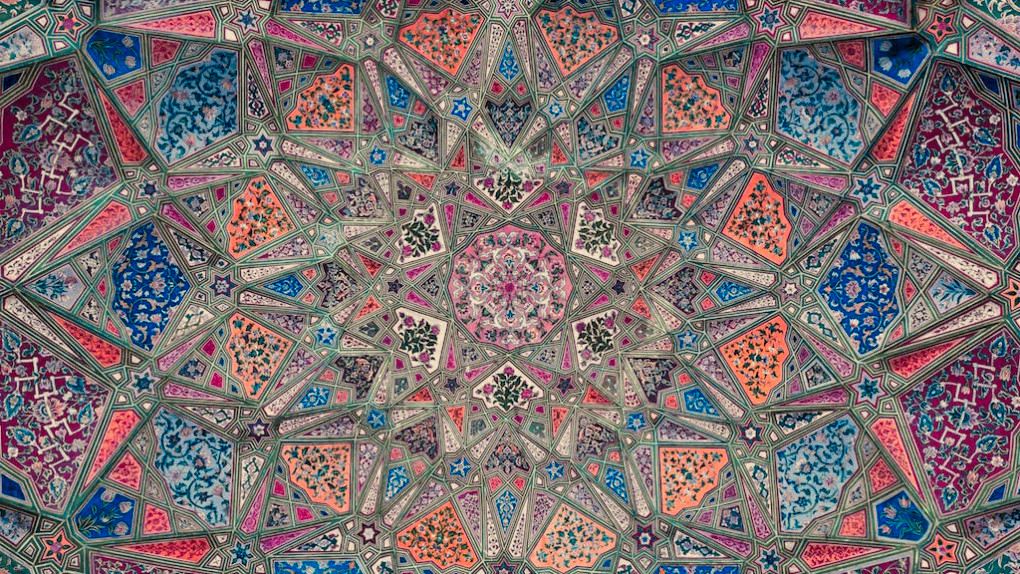

In the grand mosques of Arabia (and there are many such enormous structures) we find places of worship where the figure of man is scripturally unacceptable. I have always had the vague understanding that depictions of Muhammad himself are "haram", but in reality depictions of any holy-men are discouraged and won't be found in any mainstream mosque. In fact you will find no human depiction of any description in most of them, nor animal nor fish nor tree nor rock. Mosques are in fact free from any depiction of the world as we generally know it. But these Mosques are by no means free from decoration, they are some of the most lavishly ornamented places I have ever seen; there is no attempt at a Calvinesque minimalism here. Instead Mosques utilise decoration in the form of pure geometry: kaleidoscopic patterns autistically constructed with a rule and compass, all adorned with painstakingly devised calligraphy to fill every cranny in a satisfyingly complete way. The overall effect is overwhelming and incomprehensible, you don't know where to start looking. Without the figure of a person to ground you all sense of scale is thrown off: is this meant to be a depiction of the universe? A grain of sand? God?

^ The altar of the Grand Mosque of Muscat (I'm unsure if you can even call it an "altar").

^ The altar of the Grand Mosque of Muscat (I'm unsure if you can even call it an "altar").

Shown above is part of the most impressive Mosque I have visited, the Grand Mosque of Muscat in Oman. Unlike most of the largest Christian creations, the largest of the Mosques are all very new, springing up from the fortunes gained off the black-nectar. The Mosque consists of a main compound surrounded by formal gardens, the principal square building surmounted with a huge dome made possible by the magic of iron rebar. Around it five enormous minarets (is that an oxymoron?*) loom like watchtowers: the speakers which play the (incessant) call-to-prayer five times a day are loud enough to be heard across the entire city of Muscat. Inside the huge square expanse is covered in a massive rug (the second biggest rug in the world apparently), which is naturally decorated with the hallucinogenic Persianate fractals you'd expect. The dome is supported by four elephantine columns which oddly obstruct your view of the room as a whole, unlike the more delicate columns usually found in gothic churches. There are indeed a set of windows around the base of the dome which let some light in, but the main source of illumination is the ten-tonne chandelier which hangs in the centre, emitting an electric flame of an intensity second only to the Empyrean-Almighty. Running around the entablature of the room is the most ornate chicken-scratch I've seen outside of Japan. The Quran in its entirety enscribed in a cursive Arabic so obtuse you need a degree in divinity to even comprehend it (or so I eavesdropped from a nearby tourguide). I spent a lot of time looking over it, even though I obviously couldn't read any of it. It was impressive how the words had been warped into such a pleasing visual composition without, I assume, any degradation to their doctrinal validity. At the western end of the hall was the main altar as depicted above (west because everything is orientated toward the Kaaba as all mosques are), it made up the centre of the kaleidoscopic whirlpool, the crescendo of the ordered chaos. But although it was the climax, it is also nothing at all. No ceremony takes place here, no divinity is ascribed to it. Rather it is just an elaborate pointer to kneel towards so that you are sure you are facing Meccawards.

^ The mirrored courtyard (sorry its vertical...)

^ The mirrored courtyard (sorry its vertical...)

Before the main portal is this courtyard surrounded by colonnaded cloisters, separating the main (male) hall from the far more modest female hall opposite. In a church courtyard you might expect to find the graves of particularly notable persons, or perhaps a statue or two. But here is nothing. A simulacra of the void made by polishing the marble floor so smooth that it reflects light like water. It was so perfect that nobody seemed brave enough to step foot on it despite there being no reason you couldn't, instead everyone walked all the way around the outside to get to the main room. This is the flipside to that cacophony of patterns found inside: oblivion. Our own "modern artists" in the West have come to similar conclusions. To depict the universe is to go down of two paths: keep adding elements until everything is drowned in an infinite discordance, or just leave the canvas blank. Both end up with a similar effect, and interestingly it seems Islam worked this out a millennia before Pollack or Malevich.

*It is apparently not an oxymoron. The "et" on "Minaret" is not a diminutive, but rather just part of the baseword as loaned from Turkish. The existence of a larger form of tower, "the Minar", is still unverified.As you can see in the photo of the courtyard, the one thing that is common between this place and somewhere like, say, Salisbury Cathedral is the fundamental use of the gothic arch. It is, however, utilised in a very different way, with there being very little actual overlap between the architectural orders of European-Gothic and Pointed-Arabian. But it is almost certainly true that the idea for the "gothic arch" came from the crusaders visiting Arabian palaces in their Holy Land gap-years. For those who don't know, the gothic arch was the principal change which propelled North-European architecture from the Roman-esque to the Mediaeval Gothic. It is not simply a pointy version of a round-arch, but a careful mathematical construction which greatly improved the weight-bearing ability of buildings, thus allowing for much thinner masonry and much taller structures (it was only improved upon by the discovery of the hard-to-construct catenary arch). Simply, the gothic arch is constructed by the arcs of two circles, each centred on the circumference of the other. This construction also produces an equilateral triangle meaning it can be repeated around itself as you like. While later scholars of Christendom would extrapolate on the study of what would become known as "sacred geometry", it is a science which holds much greater value in Islam. Geometric patterns such as the gothic arch are coherent with that uniquely Islamic overlap between theology and aesthetics in a way which is (ironically) very ungothic. While "gothic" (the most Christian of the artistic schools in my opinion) is human in scale and naturalistic in its imperfections, Islamic aesthetics rely on strict but simple rulesets and a "perfect" underlying structure. I believe this worldview is in line with the history of Islam. The perfect nothingness of the desert and perfect order of the night-sky by which they navigated. The discipline and ruthlessness of the divine jihad, bringing order to chaos. In such a worldview we mere imperfect mortal humans have no place, and must simply bow to the complete domination of the geometric god.